South Sudanese women have among the highest fertility rates and maternal death rates in the world, yet cultural norms still frown upon contraceptives—even to make pregnancy and birth safer for women.

In light of this paradox, University of Michigan researchers wanted to better understand these Sudanese women’s ideas about contraceptives and family planning in order to address the challenges to providing contraceptives and better child and maternal care.

Between 2013 and 2017, researchers from the U-M School of Nursing conducted six Home-Based Life Saving Skills workshops with 68 Sudanese women––one group in South Sudan, and five in Northern Uganda refugee camps, where many Sudanese women were driven during the war, said Ruth Zielinski, U-M associate professor of nursing.

The researchers found, overwhelmingly, that use of modern family planning methods wasn’t acceptable in the community, but that despite that, women still wanted to learn about it.

Zielinski became interested in this population of Sudanese women about five years ago, when she was contacted by U-M graduate John Musick. Musick and his wife, Rev. Denise Scheer, had been doing nonprofit mission work in developing countries since 1994, and in 2003 they decided to broaden this to include villages in the Sudan.

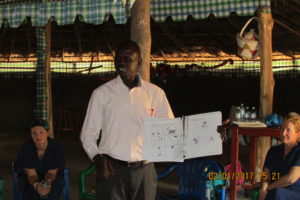

The family planning and child health workshop for Sudanese women in Ugandan refugee camps.

Their group, the South Sudanese Leadership and Community Development Group, uses grass-roots community development to teach marginalized Dinka women in Northern Uganda refugee camps basic skills for self-sufficiency.

Musick said that while learning about the population and prioritizing the community’s needs, maternal and child care topped the list.

“One of the first things we heard when we talked to the community was, ‘We’re dying in childbirth,'” he said.

So, Musick contacted Zielinski, a nurse midwife, to help him develop and implement the family planning and maternal and child health component of SSLCD’s mission.

“As a nurse midwife I had been very interested in global women’s health,” Zielinski said. “Once I started going there, it was hard not to go back. They are so smart and so interested in learning.”

Participants leave the workshop with picture cards so they can share the information with the community.

She said family planning must be approached much differently there than it is here––where for the most part, birth control is not taboo. Also, many of the women can’t read, so this is a picture-based program that focuses on identifying and preventing problems during pregnancy and birth.

“Family planning must be incorporated in with the bigger picture, which is education around pregnancy and birth and infant care,” Zielinski said. “You can’t just go in there and start talking about family planning and contraceptives.”

For instance, very few of the women in the study even knew about modern methods of contraception, and while some had heard of condoms, most didn’t know how to use them. There were also firmly held cultural taboos regarding contraceptives—that only “loose women” used birth control and that contraceptives would decrease the population.

Despite this, women were still interested in learning about family planning, and even wanted to share the information with others, Zielinski said. They acknowledged that times were changing and that their children would learn about family planning, which motivated them to learn as well. However, they didn’t believe it was acceptable for their daughters to use contraceptives or have sex outside of marriage.

The primary method of family planning for the women was abstaining from sex while breastfeeding, to space children apart. This cultural norm is slowly being abandoned, which will negatively result in more pregnancies that are closer together, Zielinski said.

Daniel Kuir Ajak, interpreter, explains what to do when women encounter a problem during labor and birth. In background, Alisha Macrhand, midwifery student, and Ruth Zielinski, associate professor U-M Nursing School.

The women believed that having children too young, too old or too close together wasn’t good, but they felt that having lots of children was beneficial because that insured at least some would survive despite the high mortality rate.

Zielinski said that a critical component to reducing unplanned pregnancies is to empower Sudanese women in the community, a sentiment Musick echoes. This is a highly patriarchal society where women are expected to submit to their husbands, and many women––especially younger women and adolescents—feel they can’t refuse a marriage proposal, and adolescents have more complications during pregnancy.

Women in the study suggested that men also take the HBLSS workshops, and Zielinski said researchers are developing a pilot project for men that will be presented in the fall.

Zielinski and Musick hope their two groups can return to Northern Uganda together in early 2019.

The study appears in the journal Clinical Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine.