For long-time Ishpeming resident Lizzy Nevala, her town is a tale of two cities: The one where those lucky enough to have well-paid jobs in mining are doing great, and the one where residents need to decide whether to pay rent or buy food.

More Info

“You have people that are doing real well and are living in town and paying these exorbitant prices. And there are people who are living on minimum wage or if the mines shut down or get laid off and then they’re in trouble. It’s either feast or famine here,” said Nevala, director of operations at the Ishpeming Salvation Army in Marquette County, who for 20 years has been working with the organization providing support for residents in need.

Now, University of Michigan researchers are partnering with the Michigan Farm Bureau to understand the unique challenges rural families face when accessing nutritious meals through food assistance. Often, these programs are designed without the user perspective in mind and are implemented in ways that many families do not find accessible or respectful.

“While a lot of efforts related to solving hunger focus on urban settings, rural families face food insecurity as often as urban families do,” said Kate Bauer, associate professor of nutritional sciences at U-M’s School of Public Health who leads the U-M-based Feeding MI Families program.

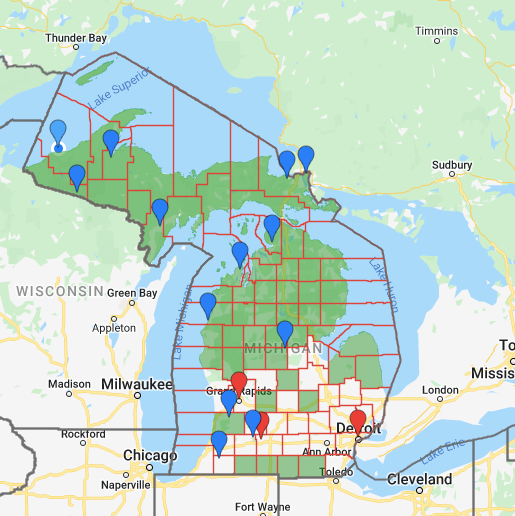

“If we look at Michigan’s Top 10 counties for food insecurity, eight of them are in our rural counties, including all of northern Michigan. By elevating parent voices, we hope to build an equitable and responsive nutrition safety net for Michigan’s rural families.”

Michigan Farm Bureau recently announced its focus on the eradication of childhood hunger in the state. The organization has worked with U-M in the past to study health care access issues in rural settings.

“We’re seeking a sustainable approach to eradicating childhood hunger. Feeding MI Families will help us better understand the systemic causes of food insecurity and low food access for rural Michigan families, and will deliver recommendations for how our organization can strategically invest in rural Michigan,” said Tom Nugent, director of Human Resources at Michigan Farm Bureau and head of the organization’s For-Purpose Task Force.

“When we looked at food insecurity in Michigan, we saw the hardest hit counties were in the northern part of the state including the Upper Peninsula. We knew we had to focus our efforts there to learn more about this problem and be better able to tackle it long-term.”

Feeding MI Families: focusing on both urban and rural families

At the beginning of the pandemic Bauer, an epidemiologist, worried about the many families who were experiencing hunger as schools and day cares closed, people lost their jobs, and the economy came to a halt. She started working with local and national experts to identify strategies to ensure that all families were able to consistently access nutritious food.

In these conversations, Bauer noticed discrepancies between what families wanted and what food assistance programs provided. At the same time that many families were saying they didn’t have enough food to eat, some programs weren’t being used to their fullest. The underlying problem, she would find out, was simple: The people making decisions about food assistance were not consistently talking with the beneficiaries of these programs.

To address this gap, Bauer and her team developed Feeding MI Families. It began with a focus on Michigan’s urban families supported by a $400,000 grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. With this funding, the project has engaged parents from Detroit, Grand Rapids and Battle Creek who have experienced food hardships, building their capacity for advocacy and community-based research.

Over the remainder of 2022, these parent leaders will conduct surveys and interviews with 750 families in their communities. Of particular importance when working with these urban families, many of whom are Black, Latino, Middle Eastern and/or new immigrants, is how racism and discrimination has affected their ability to access food and food assistance—and what can be done to eliminate these serious barriers to health. The ultimate goal of this work is to develop parent-driven recommendations for food assistance that feeds families with dignity and respect.

With the Farm Bureau, Bauer’s team will replicate its urban work across Michigan’s 57 rural counties—including every county in the Upper Peninsula and northern lower Michigan. This month, parent leaders from these counties will survey 600 rural Michigan families to document their expertise and ideas for change. The Farm Bureau will use their recommendations as a road map for future investments to eradicate rural child hunger.

“Many Michigan families are still struggling, perhaps even more so than during the early days of COVID-19. The pandemic is ongoing, the federal aid mostly gone, and food prices and gas prices continue to climb,” Bauer said. “Many parents are talking about the current ‘food crisis,’ which they do not expect will end anytime soon. In partnership with the Kellogg Foundation and Michigan Farm Bureau, Feeding MI Families is helping us understand how to move forward and best meet these families’ needs.”

Different settings, different needs

According to Feeding America, 2.2 million households in rural communities face hunger and rural communities make up 87% of counties with the highest rates of overall food insecurity.

Salvation Army’s Nevala said during the pandemic many mom-and-pop shops that were the only grocery store in a town closed, leaving whole communities without fresh produce, or having to drive over an hour to the next grocery store. For others, the influx of tourists and college students meant rent increasing past what people on fixed incomes can pay.

Residents might be too proud to ask for help, unable to fill out the forms online, or unable to travel long distances to fill out the forms in person. And then there are the products that food stamps won’t cover, but that are also needed for people’s well-being like toiletries, diapers and cleaning supplies.

Stigma and shame are consistent barriers to using food assistance and accessing food in rural and urban areas alike. For example, in the UP, communities are tightknit and a new mom might be too embarrassed to go to a food pantry or sign up for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC, benefits because her neighbor is working at the front desk.

“Basically, we want to learn from parents: What would be the ideal way to help them feed their family with dignity and respect in a culturally appropriate manner?” Bauer said. “We have to engage with rural Michigan families to understand what their challenges are so we can help solve them. That’s what we’re hoping our partnership with Farm Bureau will accomplish.”