David Burke describes a scenario that could be one outcome of the work he and colleagues are doing with their project, Deep Monitoring, which just received a large second infusion of funding from the Third Century Initiative.

“Is that pen from U-M?” he asked this interviewer furiously scribbling his comments, who answers in the affirmative.

“I’d like to see every doctor’s office with a basket of temperature monitoring devices instead of pens that they hand out to patients and say, ‘Here these are free. Take three, one for your upstairs and downstairs bathrooms, and one for your glove compartment,’ ” said Burke, professor of Human Genetics, U-M Medical School.

The goal: to allow patients to send important, trusted data to a physician that can help monitor a health condition without the need for face-to-face interaction.

Burke and colleagues have just received a $1.4 million Phase II, three-year grant from the Third Century Initiative to develop, test and deploy such a device and other technologies that could be used to monitor chronic disease in the elderly and underserved populations in the United States and elsewhere.

“The challenge is developing devices that are easy to use so patients of all skill levels will use them and have the data be high enough quality that the medical professionals will trust them,” said Mark A. Burns, T C Chang Professor of Engineering, chair and professor, Department of Chemical Engineering.

The full name of the project is “Deep Monitoring Chronic Disease in Underserved and Remote Populations.” For this second grant the team specifically will target low-resource locations in Michigan, rural Jamaica and Ghana.

Their proposal calls the project “a balance of academic research novelty and real-world implementation into the Michigan health system and the developing world.”

Even with the rapid advancement of technology, mass producing inexpensive health monitoring devices is a relatively untapped area.

“There is a gap in technology because many who develop consumer products are reluctant to go into these areas. The commercial developers don’t see the value of it,” Burke said. “There’s not much profit—there’s value to the health care system but not a lot of profit in low cost individual devices.”

At least not now, he said, until someone does it first.

“So we asked, can we look at the technology we have and use the power of U-M—the clinics, physicians, engineers, and public health and social sciences researchers? Can we use our resources and our knowledge of engineering, manufacturing and manufacturing infrastructure to target consumer devices that yield quality data that physicians can believe?

“That’s where our approach is different. We’re beginning with the doctors as the gatekeepers of new medical technologies, not the consumer.”

The technologies, some of which already have been developed in Phase I and are ready for further testing and refinement are: wireless temperature and sound sensors, wireless aqueous chemistry (urine) detectors, quantitative 3D eye imaging and recording systems, and interactive personal health interfaces for the elderly.

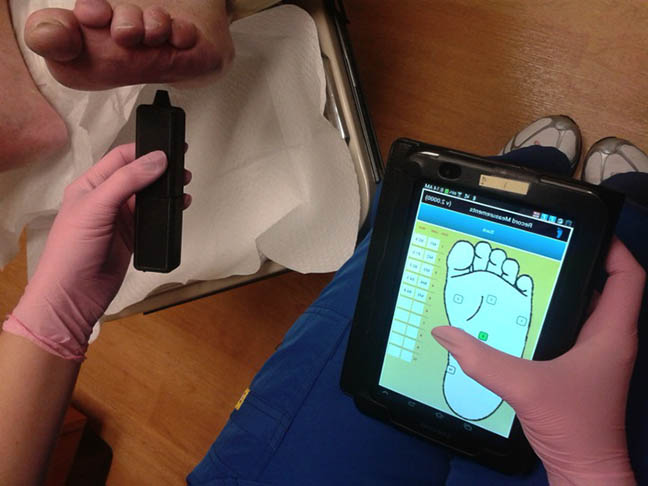

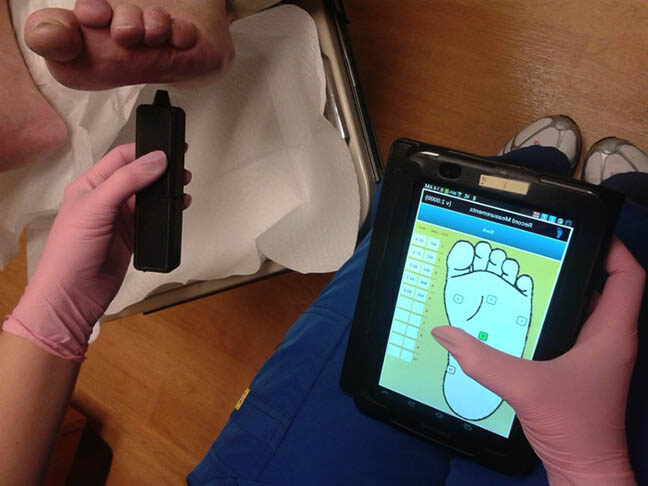

The temperature device already developed and currently at a cost of less than $5 is being tested as a means to record limb temperatures that could signal inflammation in diabetes patients.

The sound sensor, at present running under $20, serves as a remote stethoscope, allowing health care professionals to monitor breathing for patients.

A device currently coming in at around $40 is a first-generation urine chemistry sensor for analysis of kidney function, another tool that can be used for monitoring patients with chronic diabetes who are at risk for kidney failure.

During Phase I, the team also assessed various eye-imaging devices in clinical environments in rural Jamaica and at the U-M Kellogg Eye Center, and then, with Michigan-based commercial partners Medar Inc. designed a preliminary system for high-resolution 3D eye imaging and measurement. When optimized, the system might also be used to monitor reflexive and directed neurological responses, and detect changes in blood flow that could signal eye disease.

The testing and development of these health monitoring tools occurred over 15 months, with support from an initial $252,000 TCI grant. The goal of Phase II is further testing and refinement, and, with hope, a reduction in the cost to mass produce the items.

Another item, yet to be developed, would involve creating an age-appropriate technology interface that would capture and quantify information from an individual using low cost sensors. This project acknowledges the challenges older adults face with current technologies like smartphones and tablets, so it will involve use of more conventional television monitors and an adaptation of video game-like motion recognition interfaces.

In the scheme of things, Burns said, these are not complex technologies. But they are a start to show that good quality data can come from devices and systems that don’t have to cost a lot, and that have the potential to change the way health care is delivered, particularly in remote areas.

“We are not developing something that can’t be done other ways. We are trying to use existing technology and new technology (when we have to) to build complete working units at extremely low cost,” he said.

The Global Challenges for a Third Century grant program seeks to inspire ideas about how to tackle some of the world’s greatest problems. The grants come from a $50 million fund dedicated to transforming teaching and scholarship, as U-M approaches its bicentennial in 2017 and plans for the university’s third century.

Burke said the U-M funding sends a great message to faculty about trying new things when conventional funding is not possible or harder to come by.

“The Third Century Initiative gives an importance to the project, and it’s significant that the U of M has searched and asked its faculty, ‘what do you want to do?’ That official recognition is going to help a lot as this project moves forward to perhaps seek other funding,” Burke said.

“It also will encourage other faculty to talk and work with us, knowing it’s academically validated.”

Other team members are: Dr. Joseph Myers, optometrist, University Health Service and co-founder of the non-profit Eye Health Institute; Dr. Maria Woodward, assistant professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, U-M Kellogg Eye Center; Dr. Akinololu O. Ojo, Florence E. Bingham Research Professor of Nephrology and professor of internal medicine, Medical School; and Dr. Paula Anne Newman-Casey, assistant professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, U-M Kellogg Eye Center.