Counties that scored 60 or more were considered to have a passing grade; those with 40-59 most often gave correct information but may not have done so quickly or easily; those with 40 or fewer points failed.

Students that worked on a research project at three different times over five years all had pretty much the same thing to say: tackling a “real life” legal issue was an experience that continues to impact their lives today.

For one it led to a career decision. For another it dovetailed with an interest in reproductive rights and reproductive health, areas of current study. For the third it influenced her work offering legal aid to people who can’t afford private attorneys.

The Advanced Gender and Law seminar, taught by Anna Kirkland, Arthur F Thurnau Professor and associate director of Institute for Research on Women and Gender, and associate professor of women’s studies and political science, took on a project in 2010 to conduct a statewide assessment of how well county courts were communicating to young women about the judicial bypass law that allows minors to seek permission to get an abortion without parental consent. They conducted the same study in Florida in 2012 and updated the Michigan survey in 2015.

“Engaged learning with legal topics is hard because the professional side of law is very closed off. It’s against the law to practice law if you’re not a licensed attorney,” Kirkland said. “But students can blend social science research and the law, and do things like interview employees about workplace laws, observe family court, or test the judicial bypass provision.”

“I wanted them to do some research work at the point when law touches the lives of ordinary people, and luckily those spaces are more open as interactive learning sites.”

Students from the class adapted a survey instrument from Helena Silverstein, professor and department chair, Government and Law Department at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania, who had conducted similar research in other states and was a guest presenter in Kirkland’s class.

The students called the courts in 83 Michigan counties, asking a series of questions about how a young woman would go about seeking a waiver.

The final report from that first class showed 54 percent of the courts received a failing grade on the survey that measured both the quality of the information and court employee behavior in response to the inquiries.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Krupar, from the 2010 class, is now a lawyer who works for Legal Aid Society of Mid-New York.

“I think this presents and amazing learning experience that five years later I can say impacted my law school learning and influences the work I do today,” Krupar said.

“Even though I do not work with reproductive rights today, at Legal Aid I’m working with people who are left out of the legal system due to poverty or other issues.”

In 2012, the class conducted a comparable study in Florida, with similar results. One of the students from this project said the poor showing among the courts there “got my blood boiling.”

“This project was one of the reasons I decided to go into law, so it’s very dear to my heart. I wanted to pursue a career where I could change the affects of laws,” said Megan Saumier-Smith, a women’s studies graduate who now is a law student at Boston University.

“For me, this was a unique experience that most people don’t get to do. I had no idea at the time it was going to be a life changer.

A follow-up to the Michigan study was just finished in 2015 by the non-profit Michigan Organization on Adolescent Sexual Health, not by the class itself, but two students that had gone through an introductory gender and law course taught by Kirkland conducted the research.

“It was a surprise to me how disorganized some of the courts were. Some courts had really long wait times. One took a half hour to get back to me. Some gave me answers that were flat-out wrong,” said Erica Liao, political science major. “It was nice to get some research experience that was meaningful to what I was learning.”

Kirkland said experiences of the three students have been echoed by others that have taken the course.

“I’ve heard from students that this project really opened their eyes to how challenging and awkward it can be when research involves things like calling strangers on the phone to talk about emotional and controversial issues, but also how empowering it was when they finished and they had results that were totally original and even shocking to them,” Kirkland said.

What the surveys showed:

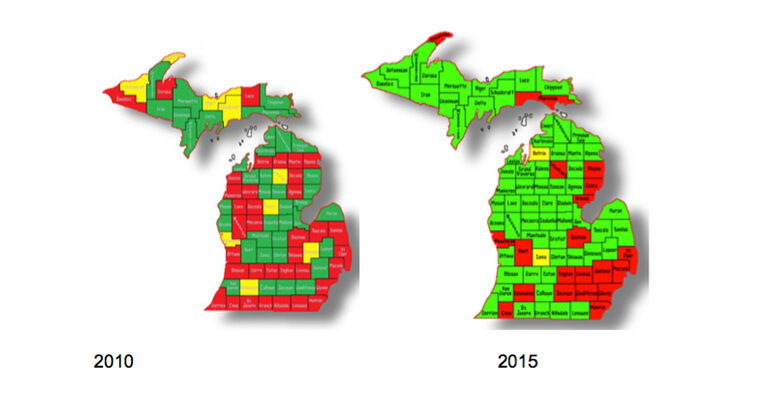

Counties in green scored 60 or more points and were considered to have a passing grade; those with 40-59 points (yellow) most often gave correct information but may not have done so quickly or easily; those with 40 or fewer points (red) failed.

The number of counties providing accurate and timely information in a helpful manner about the Parental Rights Restoration Act of 1990 more than doubled from one survey to the next. Some problems persist, however, in how judicial offices across the state respond to requests for information.

Using a series of questions and a rating system of 100 points, they found that 54 percent of counties failed in 2010, with 13 counties receiving scores of zero. The most common problems were ignorance of the law, inappropriate referrals, limited judge availability and multiple call transfers.

The study was repeated last year by the Michigan Organization on Adolescent Sexual Health, in cooperation with U-M and with funding from the National Institutes for Reproductive Health. Students from another of Kirkland’s classes conducted the calls, using the same survey with a few revisions.

This time around 26 percent of counties received a failing grade, a considerable improvement but still a concern to one of the students that conducted the most recent research.

“I know that the last time they did this study the courts changed, so I hope this time also will result in new processes and procedures,” said Erica Liao, political science student.

Overall, the judicial office personnel appeared more informed, cooperative and responsive, the research report states. The greatest obstacle in the recent survey was the need to call several courts back due to increased use of voice mail. The students also suspect that word got around that the calls were being made again, so some court employees may have brushed up on the law at the last minute.

“I conclude from the improved Michigan outcomes that our study helped create a sense of accountability,” Kirkland said. “Court employees and their supervisors realized that we might be studying them and that they wanted to improve how they performed under scrutiny.”

“It’s a credit to those courts and the leadership there to see that these improvements actually happened,” Kirkland said. “My students also deserve credit for the change because it was their intervention and their report that exposed the poor treatment. “