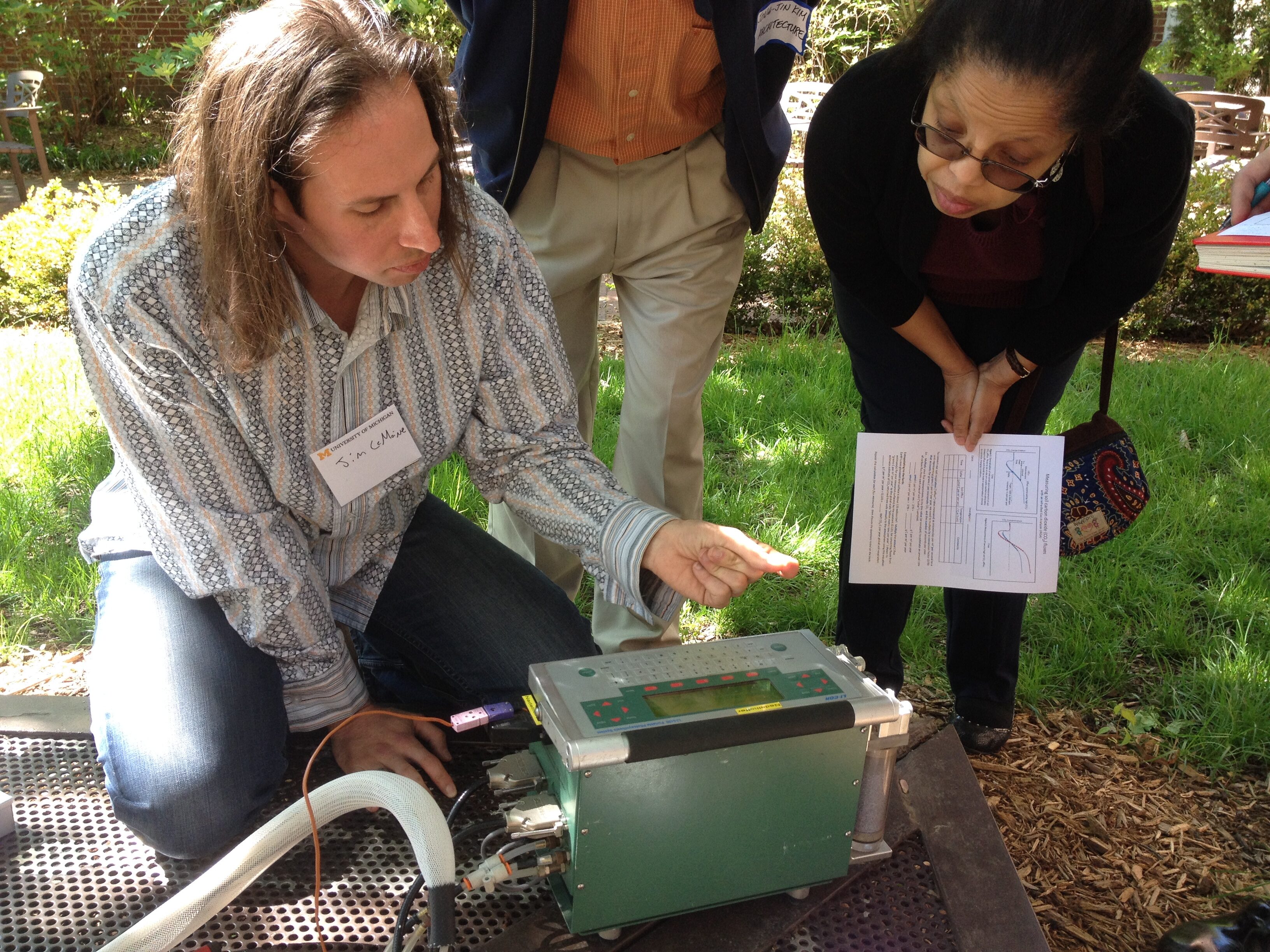

Jim LeMoine, research laboratory specialist associate, shows Addell Austin Anderson, director of the University of Michigan Detroit Center, carbon dioxide readings from the soil outside of the Michigan League. Leaders from the U-M Biological Station took faculty and staff outdoors to participate in an abbreviated experiment much like the ones students experience.

“What would it take for every student at the University of Michigan to have a high-impact engaged learning experience?” That’s approximately 7,000 experiences a year, just for undergraduates with current enrollment trends.

“What if a common element of Wolverine Experience was not just a seat in the Northwest corner of the Big House?”

These questions posed by James Holloway, vice provost for global and engaged education, reflected the theme of the May 16 Provost’s Seminar on Teaching co-organized by the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT) and Holloway’s office.

Offered semi-annually, this term’s seminar was titled “Thinking Long-Term: Next Steps for Engaged Learning at Michigan and Beyond.” It brought together 175 U-M faculty, administrators, and staff, as well as education leaders from Georgetown, Cornell and Harvard universities who helped U-M lead a discussion about the future of engaged learning at the nation’s top universities.

From left, Randy Bass of Georgetown, Richard Kiely of Cornell, Brooke Pulitzer of Harvard, and James Holloway of U-M share thoughts about next steps for engaged learning. (Photo by Steve McKenzie CRLT-Engineering)

Randy Bass, vice provost for education and professor of English at Georgetown, said his university is wrestling with the same question of where to go next with engaged learning.

“It sits in many ways on the margins of our institutions and we need to figure out how to bring it into the hearts of our institutions,” he said.

Bass said the academy over the last few years has been “letting Silicon Valley write the story of its future,” as many of the solutions have been in response to the increasingly digital world that students spend most of their time in.

“We should stop talking about tech and start talking about the learning ecosystem,” Bass said, adding that the four key principles for what he called re-bundling this form of education are: learner-centered, networked, integrative and adaptive.

“That is where you develop whole people. That’s where you develop ethical humans, capable practitioners, capable leaders,” he said.

Brooke Pulitzer, director of programs and administration at Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching, described the tension that exists between being world-class research institutions and universities invested in the engaged learning experience.

“It’s a challenge. We’re continuing to experiment with different ways to do this in a sustainable way,” Pulitzer said.

Barry Fishman, Arthur F Thurnau Professor of Education and professor of information, explains to workshop participants how gameful strategies in courses allow students to choose their own paths to learning and encourage risk-taking. (Photo by Austin Thomason, Michigan Photography)

In his opening remarks Holloway shared the brief history of U-M’s deep dive into engaged learning, which began when the president and provost in 2011 allocated $25 million to projects that showed promise to transform teaching and learning.

Since the Third Century Initiative’s Transforming Learning for the Third Century awards were announced, 140 courses and projects have been funded that allowed faculty and staff to experiment with engaged learning concepts. Twelve projects that received the largest, transformation, grants were showcased during the event.

One of the more recently funded projects led by leaders at the U-M Biostation took seminar participants outside to measure carbon dioxide coming from the ground in a courtyard area at the Michigan League, to learn about climate adaptation and to hear about the intersection of writing and science.

Workshop co-leaders used the examples to show the intent of their project, to bring science, public health, public policy, engineering, humanities and other disciplines together to address some of society’s pressing issues.

The lesson resonated with Susan Crabb, a lecturer from the School of Social work, who said she chose the workshop that seemed the least connected with her field.

“I can see social work commonalities in what I am doing through my social justice lens. I came to this because I thought, ‘Where are the connections with a biological station?’ But there they were.”

Jim LeMoine, research laboratory specialist associate, shows Addell Austin Anderson, director of the University of Michigan Detroit Center, carbon dioxide readings from the soil outside of the Michigan League. Leaders from the U-M Biological Station took faculty and staff outdoors to participate in an abbreviated experiment much like the ones students experience.

Deborah Keller-Cohen, associate dean for academic programs and initiatives, and professor of linguistics, women’s studies, and education, at Rackham Graduate School came away from one session with some ideas for Mellon Public Humanities Fellows.

She attended a workshop called Michigan Engaging Community Through the Classroom (MECC), an interdisciplinary initiative involving urban and regional planning, public policy, engineering, public health and government relations that allows students to engage with community stakeholders to address real-world problems.

The Mellon Fellows program seeks to advance doctoral students’ “knowledge and skills into all areas of public life,” according to the program website, which included an immersive experience related to their career goals.

“I’ve been thinking about ways we can incorporate some of these ideas from MECC,” Keller-Cohen said.

One program that’s already gained widespread adoption at U-M is Gradecraft. Now used with 58 courses in 27 programs, the gameful approach to teaching offers students the opportunity to choose their paths to learning. While some aspects of the course are required, there is a great deal of flexibility for students to choose multiple routes that encourage risk taking.

“This is not about making learning fun; it’s about making learning engaging,” said Barry Fishman, Arthur F Thurnau Professor of Education and professor of information, who leads the team that developed Gradecraft.

The visiting speakers agreed that part of the future of engaged learning will involve taking successful approaches and scaling them for use by others, as Gradecraft and others at U-M have done.

As to the question about offering these experiences to every Michigan student, Holloway noted that already 2,000 undergraduate students study abroad, another 2,000+ are involved in research, and more than 2,000 participate in service learning opportunities.

“It’s not inconceivable we could reach a goal of every student having a high-impact experience at Michigan.”

Funding still available for engaged learning projects

To keep the momentum going beyond the Third Century Initiative—which officially ends at U-M’s Bicentennial next year—the university is offering TLTC-NET funds of up to $1,000 for projects that assemble groups of faculty, staff or students for regular discussions about engaged learning, or to plan next steps for a previously funded TLTC proposal.

In addition, in 2017, CRLT and the Vice Provost for Global and Engaged Education will award Investigating Student Learning (ISL) grants to individuals and teams that wish to examine the impact of educational practices that promote one or more engaged student learning outcomes. ISL grants range from $6,000 for an individual faculty member to $8,000 for a faculty-graduate student/postdoc team.

The seminar also unveiled a new engaged learning website that houses an assessment toolkit, five new Occasional Papers on engaged learning goals, and examples of TLTC projects at U-M.