U-M Dance Professor Jessica Fogel is no stranger to multifaceted, multidisciplinary collaborations, but when she first proposed her latest project called “Into the Wind,” even she did not anticipate it would include so many individuals, institutions and moving parts.

“‘Into the Wind’ has been one of the most wide-ranging and complex projects I’ve ever taken on in terms of the diversity of the collaborators and the cross-regional connections. There have been many strands to integrate,” Fogel said.

What started as a U-M effort involving faculty and students from several U-M departments, including the School of Music Theatre & Dance, the School of Natural Resources & Environment, the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, and LSA, grew to include partners from Grand Valley State University’s dance and natural resources departments, and members of the Muskegon, Michigan community.

The August 22 and 23 performances in Muskegon that featured dance students, alumni and faculty from the two universities, sought to do more than entertain. They were designed by Fogel to inspire dialogue about wind as a source of energy.

The complexity of the production and the importance of the issue were what attracted some students to the project.

“It’s not just navel gazing or just history. It’s information that is relevant to now. Finding renewable energy sources is hugely important,” said Nola Smith, recent graduate from New York.

Shawn Bible, U-M alumnus and Grand Valley faculty member, said he was drawn to the project because of his experience working as a student with Fogel, and the many possibilities presented by creating wind-inspired choreography.

“Allowing my students to work closely on a project like “Into the Wind” is an enriching experience on all levels,” Bible said. “Being inspired through movement and directed by scientific research that could someday save our planet was a direct bridge between academia and life beyond.

“Engaging students in research that speaks to their lives as people inspires and sparks an imagination that I am thrilled to help guide.”

How the “Wind” blew in

Three years ago Sara Adlerstein-Gonzalez, an aquatic ecologist, began working with the College of Engineering, U-M Energy Institute and a number of other collaborators on a project to look at offshore wind in the Great Lakes. She was invited to do the environmental assessment to determine if wind turbines, when placed in the water, had any impact on aquatic life.

Although her research continues today, preliminary results showed the turbines would not disturb plant and animal life in a significant way.

While doing the work, the associate research scientist in the School of Natural Resources & Environment figured out that most of the opposition to the huge oscillating, modern day windmills was about the way they look, not about the environment.

So Adlerstein-Gonzalez decided to change the conversation. She wanted to ask: What is beauty? Is it purely aesthetic or could it be about finding alternative solutions to current ways we obtain, manufacture, store and use energy?

It was her questions that inspired Fogel to conceive of the “Into the Wind” project.

During a Winter 2014 sabbatical, Fogel planned a multidisciplinary Spring Term course that led to the performance. The thought was that the presentation could offer a way to enter into dialogues within local communities about alternative energy. She received School of Music, Theatre & Dance support and also was awarded funding from the Third Century Initiative.

An unlikely yet inspired site

Pulling up to the Muskegon location of the dance performance feels as though one has taken a wrong turn somewhere.

Overgrown dune grass covers the ground surrounding the Michigan Alternative and Renewable Energy Center (MAREC) building. A large turbine on the property spins with the wind. Across a body of water is a large coal plant, with its towering 600-foot smoke stack.

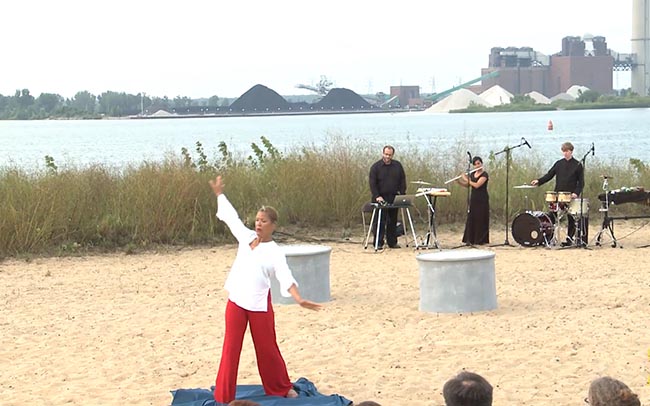

The performance begins indoors with remarks and a wind turbine-inspired dance, choreographed by Bible and performed by Grand Valley students. It then moves outdoors, through the dune grass, and onto the shores of Muskegon Lake.

The audience members are led throughout the lakeside brownfield site Pied Piper style, stopping to take in scenes featuring dance, music and poetry. The backdrop is a unique combination of picturesque landscape, raw nature and the remnants of a once-bustling industrial area.

Not your typical space for a dance performance but the right place for an arts presentation focused on wind energy, and the opportunity it may present to a city that has suffered great economic hardship over the last two decades.

MAREC was created to explore alternative energy opportunities for the community hard hit by an economic downturn, following the closure of its largest employer, Continental Motors, in 1991. That slump has continued and now threatens to deepen with the impending shutdown of the coal plant by 2016, costing the city more jobs and $1 million in lost annual tax revenue.

Dance students took a field trip to Muskegon in May for an initial exploration of the MAREC site where they would perform in August, and met with economic development and other community leaders.

“I now understand the nuances that go into environmental politics, especially at a local level,” said Alayna Baron, Ann Arbor. “There’s a lot of national coverage about environmental issues, and you hear the right and the left talk about their stances. It’s a lot more about economics than I thought. It’s about Muskegon and the people there.”

The performance not only was designed to inspire dialogue about wind energy. It also served as a time to reflect on the community’s past and future.

“I want the audience to see the possibilities for wind energy and industry, and potential innovations. I also want to acknowledge Muskegon’s spirit of resilience,” Fogel told collaborators at an early planning meeting for the event.

The local story

For one scene in the performance dancers don coveralls to pay homage to the former occupant of the site, Continental Motors, an airplane and auto parts manufacturer that ran three shifts a day with up to 10,000 employees.

While conducting research for the project Fogel and composer Dave Biedenbender interviewed four former workers from the plant. The men told stories of Muskegon’s heyday and what happened as the factory wound down.

Recognizing the power behind the men’s stories, the interview became part of the sound score.

One of the men interviewed came to the performance.

“I thought it was wonderful. I am real pleased that Jessica brought this to Muskegon. It was very touching,” said John Jolman.

The director of MAREC, Arnold (Arn) Boezaart, was a major collaborator who helped Fogel and the students with background, community connections, and facilities for the event. He served as emcee for the performance, and helped with a community discussion that followed each presentation.

“There is a profound dimension to all of us being here. Just feel the wind,” Boezaart said prior to one performance. “The profound dimension is that for 80 years this was a massive, massive industrial site. Here we are 80-90 years later reflecting with a member of Continental Motors.

“There is a certain magic and melancholy to being here.”

Channeling the wind

Just as the testimonies from the workers were integrated into the soundtrack and narrative, so were the words of people on both sides of the issue of offshore wind turbines.

The wind itself also was heard as Biedenbender and colleague Robert Alexander took data recorded on a buoy in Lake Michigan and used a process called sonification to create some of the musical score.

“It’s the world’s coolest and most complex wind chime. This is one of those examples where science is enabling us to experience art,” Biedenbender said.

LSA faculty member Keith Taylor wrote a poem for the event, and associate dance professor Robin Wilson performed a solo inspired by a painting that hangs in the Muskegon Museum of Art. Wilson’s dance invokes the four directions of the wind, a tribute to an even deeper history of the Muskegon site as former Native American territory.

Following the performances, which met with standing ovations, the performers and collaborators conducted dialogues with audience members.

David Gawron, whose father and uncles worked in Muskegon factories similar to Continental Motors, commented on the performances: “I was moved beyond words as the dancers raised the spirits of workers who once worked at Continental Motors, as they created visual sculptures in motion of work and celebration to the spoken words of retired workers, and created visions of wind power to recreate our community.”