Many University of Michigan students spent their summer actively and passionately engaged in communities nearby and across the globe. Besides creating unforgettable memories, students made a difference in the lives of people through service and research. This extra step in their academic journey—impactful and empowering summer projects—will help shape their careers.

Students from the Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering worked on dozens of atmospheric measurements in Greenland. A team from the Center for Socially Engaged Design created a first-of-a-kind community database in Ecuador.

A student at the School of Public Health worked to reduce food insecurity and its associated health problems in Detroit. A group from the School of Nursing shadowed midwives delivering babies in Denmark.

These projects are just some of the highlights of a wide range of things U-M students were involved in the past few months.

Climate science on the largest island on Earth

Lydia Gilbert and Homero Rincon Tamez were part of a group of 13 undergraduates from three universities who went on a 10-day research expedition in Greenland. The collaborative project provided rare hands-on activities for climate science students to explore authentic atmospheric and space science issues.

Group photo at Russell Glacier. From left to right: Jeremy Bassis, Perry Samson, Marc Koerschner, Alec Beljanski, Ally Finch, McKenzie Zauel, Celeste Rogers, Gwyneth Martin, Ian Kelley, Celia Warner, Homero Rincon, Abby Meyer, Lydia Gilbert, Mark Flanner, Bob Clauer, Sean Patrick.

The expedition was based in Kangerlussuaq, a community on the island’s southwestern coast, located north of the Arctic Circle. The group ventured out onto a vast, flat, treeless region to conduct experiments near the Greenland Ice Sheet, the second-largest on the planet.

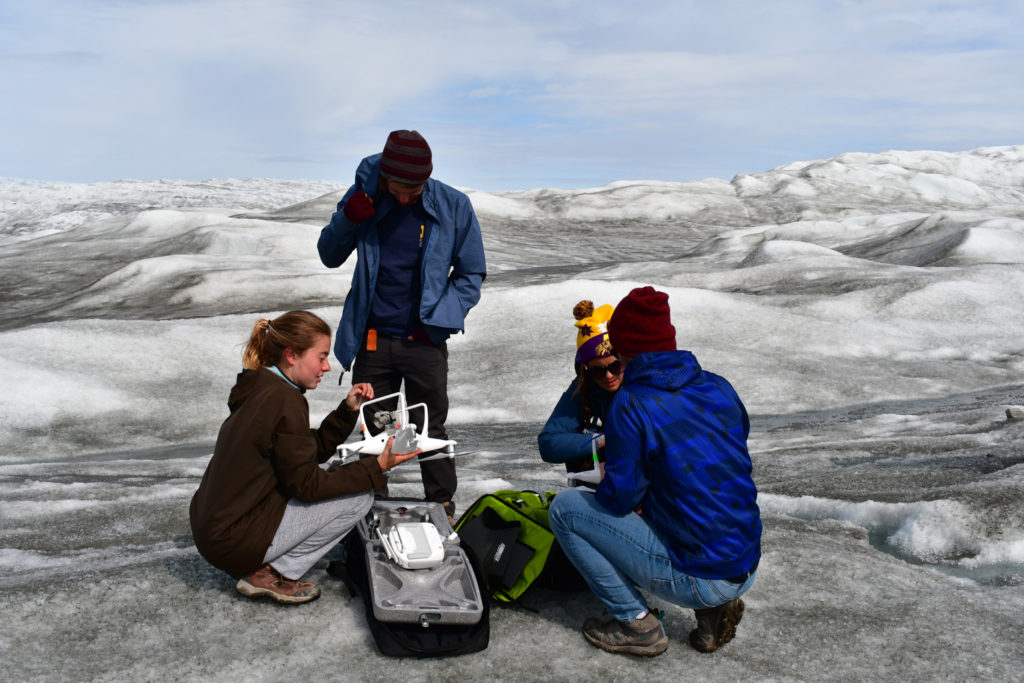

With new and sophisticated techniques and drones to map the area and take images from the ice sheets, the students worked on several measurements: wind speed, volume, temperature and direction, air quality, water flow and net radiators—how much energy the earth is getting from the sun and if the ground is getting warmer or cooler.

“Seeing the glaciers made climate change real,” Gilbert said. “I was converted to glaciology and now I want to study the internal dynamics and effects of glaciers to help understand how glaciers are calving and falling apart and how it can affect the levels rise.”

Tamez is from Monterrey, Mexico, one of the most polluted cities in Latin America.

Heading back to the LC-130 after a visit to Summit Station.

“I knew there was an air quality problem in my city and now I can really compare it,” he said. “I want to help to change it and investigate what can be done to have a good quality in Mexico and in the city I am from.”

Old-fashioned techniques were a big part of this trip as well, as the crew commemorated the expeditions of the 1920s conducted by U-M professor William Hobbs by recreating some of the observations made then with old technologies.

“Hobbs gave us the first real data on the climatic conditions in Greenland,” said Perry Samson, professor of climate and space sciences and engineering. “His research has been invaluable in understanding the regional climate systems in the Arctic, so tracing some of his steps was remarkable.”

But Samson said the main goal of the trip was to challenge the students to see what questions they would generate in the field to stimulate them to want to do more about climate change.

“My hope was that the students walked away with a renewed energy and curiosity about climate science that they wouldn’t have otherwise,” Samson said. “I also hope they will carry that enthusiasm and curiosity to other students and the community. This is the only way we can prepare the next generation of climate scientists.”

Abby Meyer, Celia Warner, and Marc packing up a drone.

Water access in rural South America

Jessica Khan, a student in environmental engineering, spent eight weeks in an agricultural community in Ecuador, conducting a needs-assessment project in partnership with the family organization Nido de Vida of Uníon La Bolivarense.

Together with three other students from the Center for Socially Engaged Design, Khan collected and organized information about water access and use in the small rural community. The goal is to use that data to identify needs and potential future project areas.

The Michigan team presents their design ethnography findings and insights at a community meeting with over 70 people in attendance.

“One of the reasons I selected this project was to explore what a water resources engineering project abroad is like, and to see if I want to pursue making these types of projects my career focus,” Khan said.

Last year, during summer 2018, a group of students from the center traveled there to identify and explore opportunities for impactful projects in the La Bolivarense community.

“It was our first opportunity for on-site research and information gathering,” said student Cameron Beversluis. “Water access was seen as one of the most important challenges, since most people rely on surface water sources such as streams and rivers, while some rely on wells.

“That is why this year the goal of the project was to accumulate, organize and distribute information regarding water access and use within the community. This data will now allow Nido de Vida and the community to better understand their current water access and use habits, and to look toward potential solution spaces related to water.”

Erin learns about hybridization techniques to improve fruit sapling growth in the Ecuadorian climate from a local farmer.

Among the recommendations the team put together: more investigations on how to move water without a gas or electric pump to minimize costs; instead of plastic tanks, the construction of cement tanks that can reduce prices; and a conservation/education effort accompanied by community building efforts.

“My experience with Nido de Vida made me more familiar with Ecuadorian culture and the specific water issues of La Bolivarense,” Khan said. “And because of my work this summer and my experience with assessing the water-related needs of a community, it will be valuable while exploring the possibility of a partnership between Nido de Vida and another student project called Aquador, where I am the co-president and design team lead.”

Around the corner

Erica Bennion, a student at the School of Public Health, spent the summer as an intern at American Indian Health and Family Services, a Detroit-based nonprofit that serves the American Indian/Alaska Native community and other underserved populations in southeastern Michigan.

Her project goal was to help the organization maximize its impact in reducing food insecurity and associated health problems, including poor mental health and obesity.

Erica Bennion – Student at the School of Public Health

“To do so, I analyzed survey data from a food provision program called Fresh Rx, in which physicians ‘prescribe’ fruit and vegetable consumption and provide monthly produce baskets to low-income patients with chronic disease,” Bennion said.

Survey results indicated an improvement in participants’ overall mental health, depression, energy level and mental capacity to go about their usual activities after participating in Fresh Rx.

Participants also felt more confident in their ability to find fresh fruits and vegetables in their community (24% increase), select quality fruits and vegetables (12% increase) and store produce appropriately to make it last (24% increase).

According to Bennion, Fresh Rx could impact even more people if it coordinated with physicians from other clinics or made care at American Indian Health and Family Services more affordable by extending the ambit of acceptable insurance.

“Many participants have limited transportation to AIHFS, so picking up the baskets before produce began to spoil was a challenge,” she said. “They suggested giving vouchers for local farmers markets and grocery stores instead.”

Now, Bennion plans to pursue a career in program evaluation to help organizations like American Indian Health and Family Services maximize their efficacy.

“I am passionate about mental health and about improving food environments, air quality and access to quality medical care,” she said.

Oh, babies!

In Denmark, midwives deliver more than 90% of babies and can work completely on their own one-on-one with pregnant women. Gabriela Miles was among 10 students from the School of Nursing who spent a month in Copenhagen shadowing midwives.

“In the U.S., most deliveries are by OBs who come in just for the actual delivery as opposed to total care,” Miles said. “Most of us had a particular interest in women’s health, OB specifically, and were interested in what we could learn from this holistic care process.”

“In the U.S., most deliveries are by OBs who come in just for the actual delivery as opposed to total care,” Miles said. “Most of us had a particular interest in women’s health, OB specifically, and were interested in what we could learn from this holistic care process.”

The trip—which consisted of lectures, two weeks of clinical hours and discussions on the Danish system—gave students the opportunity to experiment with the midwife approach and potentially apply some of the techniques in the U.S.

“This experience taught me how I can help empower women as a nurse,” Miles said. “During labor, you can be the person who advocates and helps moms to have the best experience they can, so they don’t look back traumatized on what happened.

“What I took away from this and want to bring to my future career is a movement toward not fearing birth. I want to educate people so they can embrace this beautiful and natural process. Birth is a natural process and not a medical condition. These women are not sick, they are doing something extraordinary.”