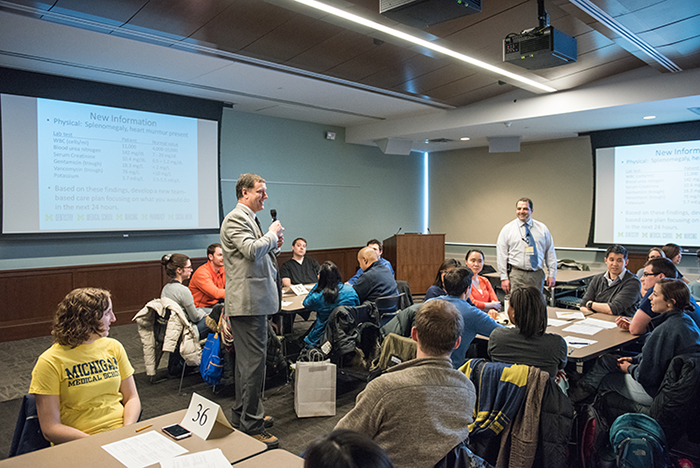

Professor Bruce Mueller, microphone in hand, sounds and acts a bit like a game show host as he moves about the room engaging with students seated in small teams.

“Did no other groups assess nutrition?” his exuberant voice resounds through the Couzens Hall classroom on a recent Wednesday. “We have a winner over here!”

Over and over Mueller, professor and associate dean for academic affairs in the College of Pharmacy, and his teaching partner Jennifer Stojan, assistant professor of internal medicine and of pediatrics and communicable diseases, Medical School, probe teams of students representing five health disciplines: medicine, nursing, dentistry, pharmacy and social work.

Someone’s life is dependent on the students’ ability to get to the bottom of a medical complication, and Mueller and Stojan wanted to know what the students were going to do as a team to figure it out.

The mock patient had been seen in the ER following a car accident that resulted in a broken leg and jaw, both requiring surgery. He had a medical history that involved IV drug abuse that was being managed with prescription therapy; endocarditis, which is inflammation of the inner layer of the heart; and chronic pain.

The surgeries were successful but the patient did not recover as well as expected. The endocarditis recurred, requiring him to go home with IV antibiotics in addition to pain medication.

This was week 2 of the exercise, and students found out the patient’s home treatment was not successful. His partner reported that he was getting more lethargic, had poor appetite and was losing weight. As the exercise went on students learned that his kidneys were not working properly and he had stopped urinating.

“How many people thought there was a medication error?” Mueller asked, after the teams had gone through numerous scenarios. About half of the hands went up across the room. “Now how could that happen?”

At the same time Mueller and Stojan were walking this group of students through the exercise, four other classes were taking place in other parts of campus, with teams tackling similarly complex cases, all with a goal to open their eyes about other patient care perspectives.

“I came into it thinking I knew about what other roles were—specifically medicine and nursing,” said Jacqueline Dufek, U-M nursing grad and practicing BSN who now is a student in the School of Public Health. “I realized that I don’t know a lot of things, which is good and humbling.”

Dufek’s classmate Mary Karina Dostie, a 3rd year dental student, agreed.

“Knowing more about the other professions is really opening up my eyes to what I should be thinking about with comprehensive patient care, and I appreciate the different perspectives,” Dostie said.

Team-based Clinical Decision Making is being offered for the first time this semester to more than 250 students from the College of Pharmacy, School of Dentistry, Medical School, School of Nursing and the School of Social Work, and is led by faculty representing each school or college. This course is the beginning of a broader Interprofessional Education (IPE) effort on campus to transform the way that health professions students learn.

“In our educational system, students in the health sciences are still educated in silos. When they enter into practice they work in interdisciplinary teams,” said Gundy Sweet, clinical professor of pharmacy and director of the course. “This course helps us to break down barriers and see the world from a different perspective.”

The IPE effort recently received a 5-year $3 million Transforming Learning for the Third Century grant from the Third Century Initiative to engage students in learning and change the way faculty teach more than 4,000 students in all of U-M’s health professions.

“Students have worked with challenging clinical situations that bring in their personal values and beliefs, and decisions need to be made about how to proceed as a team,” said Michelle Pardee, clinical assistant professor, School of Nursing.

The goals of the program align with efforts by organizations like the Institute of Medicine, which has pushed for cross-communication and interdisciplinary teams to improve patient outcomes, safety and use of health dollars, Sweet said.

Additionally, an interprofessional educational experience is required by accreditation bodies in various health disciplines, she said. Some universities fulfill this with workshops, short-term programs, and the like. The U-M course is believed to be the one of the largest, most complex undertakings to address this new reality.

“This course will improve the dental students’ ability to contribute to interprofessional care, especially in external community-based clinics,” said Dr. Mark Fitzgerald, associate professor in the School of Dentistry.

Dr. Joe Hornyak, clinical professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, Medical School, said while working with other faculty to put the course together, he learned much about the other disciplines as well. To bring home the concept of interprofessionalism, the course is taught with faculty from two different disciplines in each classroom to model how the professions can work together.

“Everybody is expected to function as a team but you’re kind of thrown into a team as you finish your education,” Hornyak said. “It’s been really nice to see the students begin to teach each other. A lot of what we do is facilitate communication between different people.”

Debbie Mattison, lecturer II in the School of Social Work, has enjoyed watching the students develop camaraderie and respect as they learn from one another.

“We’re better clinicians when we know how to use our team members and collaborate with them,” Mattison said. “It’s been exciting to hear students say things like, ‘I would never have thought of that.’ Or ‘because this person is on my team I now know that I need to look for that when I am providing good care to patients.’ ”

Back in Mueller’s classroom students spent quite a while going through the evidence to try to figure out how the wrong dose of the drug used to treat the endocarditis was administered.

“This was a horrible handoff. Who should have caught this?” he asked.

In the end, teams talked about how they would break the news to the patient and his family.

“If you listen, it’s really noisy in here. It’s because they all want to be heard in their roles,” Mueller said about their discussion.

“This is very relevant to us in the medical field,” said Daniel Kim, 3rd year medical student. “Having a discussion all together about patient cases has been very enlightening. We see that in the hospital as a student but we don’t really get to partake in that fully.”

Although the students might never know the answer to what went wrong in this mock mishap, the one thing they were clear on: it was a failure at multiple levels, and the kind of team discussions they were having could help prevent something like this from happening to their future patients.

“This is the future of health care,” Dufek said. “And if we really want to make a better system then this is where we need to start.”