The students sit at small tables of four to five, separated by white boards. They wait for questions to come up on their electronic devices, which are tapped into a program that knows which student is sitting in what seat.

The graduate student instructor (GSI) decides to wait another minute for stragglers to the class on this Thursday in the Chrysler building on North Campus.

This is not an exam. In fact, this course promises there will be none of those. Professor Steven Yalisove’s syllabus for this engineering course says right up front: “No Lectures, no exams, and no graded homework—but you will learn much more…”

Instead, this is a weekly test to check how well students understand the material in required reading.

“The individual round has started. You have 30 minutes. Good luck,” GSI Kevin Golovin says over a microphone from the back of the class. Or is it the front? The somewhat unconventional layout of the room, designed to foster collaboration, makes the answer to this question unclear and irrelevant.

Yalisove, GSIs Golovin and Anton Li, and three aides, who are undergraduate students from the previous year, monitor the students’ progress on the questions from their own computing devices using a program called Learning Catalytics.

On one question the program reveals 51 responses with 63 percent correct. On another, out of 26 answers thus far only 19 percent are getting it right.

“They’re struggling with this one,” Yalisove said of the second. But the numbers don’t concern him. Not only is this individual round just the beginning of the exercise, because after the half-hour is up they will work on the same questions in small groups, but he expects they will struggle.

“They have to fail before they learn. They have to get frustrated,” he said. “My job’s not to make it easy for companies down the road to choose the best students. My job is to teach the students.”

Feedback so far from the engaged, hands-on form of learning employed in this Materials Science and Engineering course has been that students not only learn but they retain the material. This is exactly what Yalisove had in mind.

“I really like it,” says Joe Wendrof, who earlier in the class had discovered a flaw in one of the test questions for which he received a “good catch” from the GSI.

“I am able to teach my classmates things I already know, and they’re going to teach me things I don’t know,” Wendrof said. “I definitely retain more information.”

“It’s more work on a day-to-day basis but as compensation I don’t have to spent a lot of time studying for exams.”

Lauren Kennedy agreed the different approach to learning engages her in new ways but is not without its challenges.

“I am a big advocate for alternative learning styles,” Kennedy said. “The projects in this class definitely engage you with the material. But 32 pages is a lot of reading, and sometimes it’s difficult to know which parts I should be focused on.”

She would like a few lectures but acknowledges she and her classmates have the opportunity to ask for one anytime the material gets complicated.

In fact, that too is spelled out in the syllabus. When students want the professor to stop and “lecture” or explain a concept, they merely have to ask. Yalisove said this happens from time to time. If he senses they don’t understand he’ll stop and offer some explanation, although he said students might not recognize it as a lecture because he tries to make it more of an exploration of the material.

Yalisove, who received funding from the Third Century Initiative to develop this course, is beginning work with five other faculty members in biomedical, environmental and electrical engineering, to help them develop similar action-based collaborative approaches to teaching.

“Our real purpose here is to teach people things they’ll remember five years from now,” Yalisove said.

Golovin signals that little time is left in the group session and the volume in the room goes up.

“I know, I know. It’s lower the viscosity and lower the melting point. Lower, lower,” one student blurts.

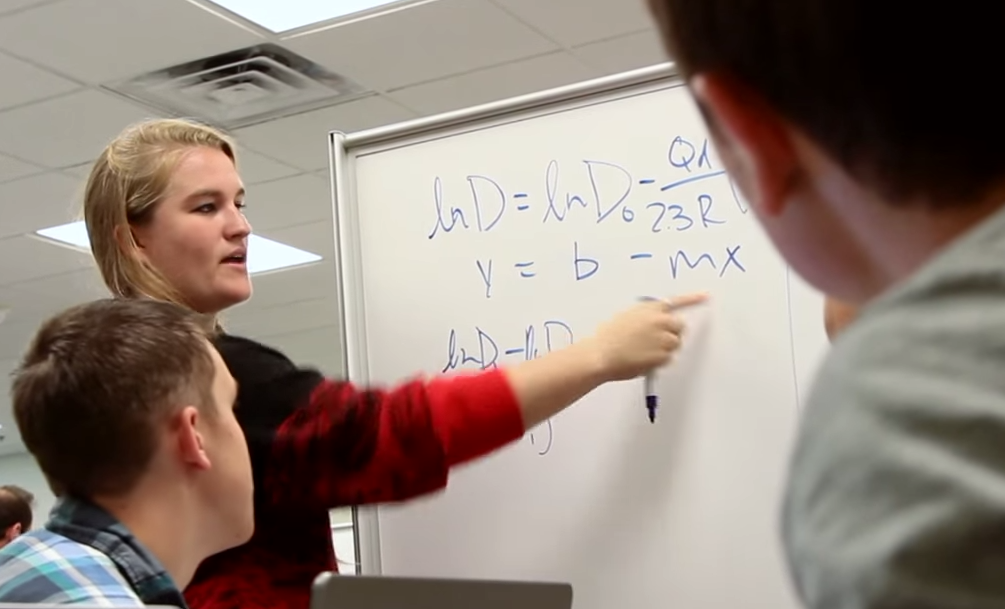

“Can somebody just write their equation on the board,” another student implores, as her team works to solve a complex problem.

At the end of the group round the students will get a grade that factors in their individual and team responses.

And that part about no graded homework; it doesn’t mean there is no homework. Students are expected to do the course readings and homework assignments, then share the latter with their peers. After class, students take their original homework and write a reflection on what they learned, complete with an evaluation of their peers, and turn it in for credit. They also are required to electronically enter a comment or question on the reading assignment prior to the class in which it will be discussed.

In addition, students work in teams on three problem-based learning projects that take the form of a presentation, poster and video.

Last year’s class created posters to demonstrate their analysis of potential materials for Captain America’s shield, Batman’s cape and Spiderman’s web. They consider all aspects: physical and material properties, product design, aesthetics, production, cost of materials—all while keeping in mind the potential failures of the materials, given the abuse they will take at the hands of these superheroes.

White board videos, billed on the syllabus as “exotic or interesting phases,” require that the students explain materials like graphene, metallic hydrogen, sapphire and nickel titanium. Groups with names like Team Awesome, Team Nano and the Fantastic Four created the videos comprised of fast-forwarded drawings on a dry-erase board.

Devon Stanke is taking the class as an elective, and said because materials science is not her area of interest she sometimes feels in over her head. But she appreciates the style of teaching, nonetheless.

“I would definitely zone out if it was all lecture,” she said.

She and Kennedy stayed after class to work on their group project.

“With lectures I might have more definition knowledge,” Kennedy said. “But I think this method is to have me wrestle with the material more.”

Exactly the point, Yalisove said.

“Most students focus on getting a good grade, not on learning the material,” he said. “We want to change that. We really want to make them learn for the joy of learning.”