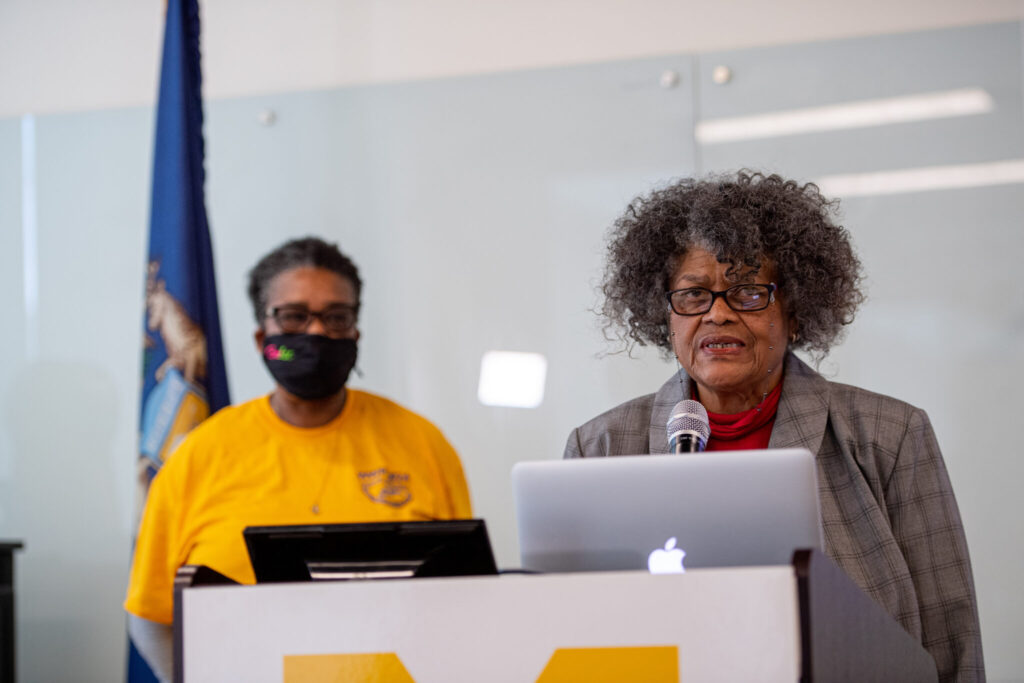

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan talks about a U-M report that finds the census undercounted Detroit residents by 8% at the U-M Detroit Center. Luke Shaefer, director of Poverty Solutions, sits at right. Credit: Eric Bronson, Michigan Photography.

Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan joined Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan and researchers from Wayne State University today to present findings from a new report that suggests the 2020 U.S. Census may have significantly undercounted Detroit’s population.

Over half a trillion dollars in federal funding, including funding for programs such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program, Head Start, federal Pell grants, and highway planning and construction are allocated to states and localities based on decennial census counts. An undercount of this magnitude would result in a significant reduction in the financial resources that Detroiters and Michiganders receive.

“The independent analysis conducted by the University of Michigan and Wayne State is incredibly impressive and deeply troubling,” Duggan said at a news conference at the U-M Detroit Center. “This report makes a compelling case that the 2020 Census was conducted so poorly in Detroit that it may have missed tens of thousands of residents, costing the city hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid for programs Detroiters badly need. We will be pursuing a remedy for this clear undercount and are in the process of determining our approach.”

Each year, the Census Bureau releases an official estimate of the residential population of every municipality in the nation. In 2020, the census counted a population of 639,000 in Detroit. When compared to the census’ 2019 estimate of 670,000 residents in Detroit, this marked an anomalous single-year decline of 31,000 residents, or about 5% of the 2019 estimate.

According to the report, “Analysis of the Census 2020 Count in Detroit,” a population decline of that size over the course of one year would be out of line with Detroit’s recent population trends, as well as trends in other cities of similar sizes, with similar economic histories and with similar demographics.

“It is implausible to think the city’s population declined by 31,000 residents in one year, so we are conducting research to examine how this could have happened,” said Jeffrey Morenoff, U-M professor of sociology and public policy and faculty affiliate of the U-M Population Studies Center and Poverty Solutions.

“We noticed that the 2020 census counted far fewer housing units compared to the 2019 estimate, so we conducted an audit of housing in 10 census block groups and found that the census undercounted the number of occupied housing units in these areas by about 8%.”

To better understand whether there was an undercount in the 2020 census estimates of Detroit’s population, researchers analyzed vacancy estimates from the 2015-2019 American Community Survey and occupancy estimates from the U. S. Postal Service for a diverse set of 10 census block groups; five of the block groups were areas with relatively high rates of occupancy and homeownership, and five of the block groups had higher vacancy rates and lower rates of self-response.

These analyses were supplemented by an in-person assessment of the occupancy status of housing units in the five more stable census block groups conducted by Wayne State researchers.

Each of these analyses pointed to an undercount of occupied residential units in these census block groups by about 8%, or about 964 residents in these 10 block groups alone. If undercounts of a similar magnitude occurred in a majority of the city’s more than 600 block groups, the potential undercount could be in the tens of thousands.

“The decennial census is an important part of guaranteeing the representation at the heart of our nation’s democracy. My staff from the Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies and I were proud to be a part of the Census Challenge Team in helping to achieve the most accurate census count possible for Detroit residents,” said Ramona Rodriguez-Washington, program director at the Center for Urban Studies at Wayne State University, who led the in-person canvas for the study.

Obtaining an accurate count of Detroit’s population was particularly challenging in 2020. Due to the shortened in-person enumeration period, this was the first time the census relied heavily on households self-reporting information online. The emphasis on internet-based self-reporting likely presented an obstacle in Detroit, one of the least-connected big cities in the country. Much of the city was among the 20% of census tracts with the lowest internet response rates. Indeed, Detroit had the lowest self-response rate among all cities with at least 500,000 residents.