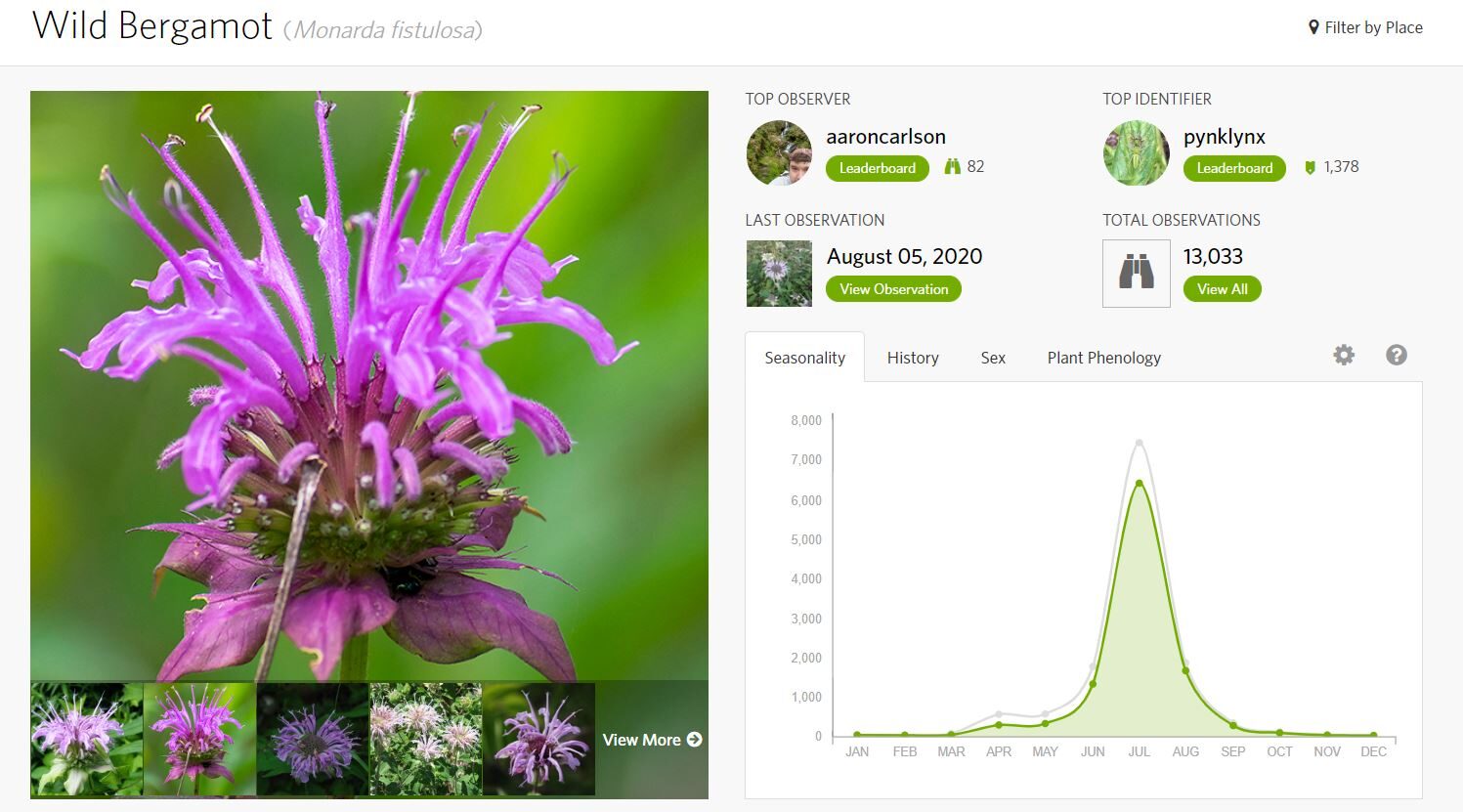

iNaturalist compiles a specimen profile with high quality photos, observation statistics, and biological information.

Instead of spending their summer at remote research stations, University of Michigan students have been conducting field research at home. Using smartphones and machine learning platforms, students have also connected to a global network of scientists.

Prior to the pandemic, enrollment for spring and summer field classes at the U-M Biological Station were at an all time high. Students eagerly planned to live away from home, at the BioStation near Douglas Lake in Pellston, Michigan.

When the university announced that spring and summer courses would be virtual, faculty and staff at the BioStation had to redesign their courses, almost all of which involve in-person and field components.

“I was definitely in ‘panic mode,’ thinking about how we were going to do all this,” Charles Davis, a professor at the BioStation, said of the stressful two-month turnaround.

He and fellow instructor Susan Fawcett debated how to virtually adapt their class, “Field Botany in Northern Michigan.” Their solution: Drop the class entirely and create something new.

“We had to completely overhaul the class and start from scratch,” Fawcett said. “There was no way to do justice to our previous curriculum in a virtual format, so we had to reinvent it.”

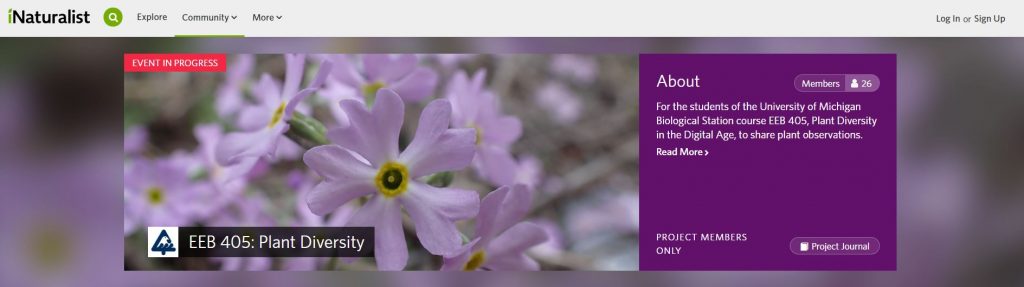

The new course, “Plant Biodiversity in the Digital Age,” emphasizes the role of technology in the study, research and curation of plants. Both Fawcett and Davis said that the class connects to larger research and museum trends of crowdsourcing data and digitizing collections.

“It’s different for sure,” said student Bella Stiver of the virtual format, noting the near impossibility of capturing her previous experiences at the BioStation.

“At the BioStation, you are living and eating every meal with your classmates, instructors and researchers. But this class was also better adjusted to the virtual format since they had that time to plan,” she said.

The instructors reached out to colleagues across the country for best practices on transitioning to a virtual format. The key, they found, is balancing asynchronous and synchronous material. For this reason, Canvas has been the foundation for housing class content.

Fawcett said they were careful to avoid the “Zoom burnout” often associated with COVID-19-induced online participation. Students have utilized class Slack channels to message and coordinate offline meetings on their own time.

Stiver explained how the students have used platforms like iNaturalist to adapt the field components of student research.

“While in the field, you take pictures of different plant parts, including the flower, seeds, stem, leaves or bark,” she said. “Then you upload the photos to the iNaturalist app along with the location of the observation.”

Through machine learning, the app provides suggestions to help students identify different species.

Over the course of the summer, the students have made 1,712 observations of 771 different species, mostly of plants with a few “pollinator” insects and fungi.

Such a tool offers both promises and pitfalls. Stiver said the app made identification simple, and she didn’t have to harm or remove parts of the plant to make a classification. Due to the platform’s public use, iNaturalist has connected the students to other scientists and amateur biologists.

Students have also learned how to trust their instincts—sometimes ahead of their new tools. While the software might correctly identify familiar species like common carrot and milkweed, it might not have the capacity to differentiate subtle variants of grass.

“It’s easy to rely on what your phone tells you,” Davis said. “Machine learning is dependent on user input. But, the technology is advancing, and, by adding data, we are helping to train these models. The more care we take in identifying the right species, the better the software becomes.”

Regionality also plays a role. Fawcett and Davis noticed the software struggled to recognize tropical species, which frustrated students taking the class from abroad. Such challenges have presented opportunities for instructors to discuss the limitations and biases in biological learning.

The virtual pivot also has opened doors to new students. After the course was offered online, enrollment doubled. Fawcett said that committing to living at the BioStation can be a barrier for some students, and, without it, more have been willing to participate.

For first-time BioStation student Alicia Lawyer, the hands-on research has provided a reprieve during an uncertain summer.

“Going outdoors was a refreshing learning experience, especially during a time stuck mostly indoors with the pandemic,” she said.

Davis echoed Lawyer’s thoughts.

“I really do believe that this engagement with nature had a restoring and calming effect in light of the pandemic,” he said. “I’m proud of the class we put together.”

Professor Charles Davis teaches botany at the U-M Biological Station.

Susan Fawcett instructs botany at the U-M Biological Station.

Davis, a professor and curator of vascular plants at Harvard University, has taught field botany at U-M since 2003. Susan Fawcett, who recently earned her Ph.D. at the University of Vermont, is a U-M alumna with interests in evolutionary biology and botany.