The web tools will help state officials identify potential hotspots as they reopen Michigan to business

University of Michigan faculty, staff, alumni and students have developed online tools designed to help local and state officials reopen the economy safely and gradually while allowing them to quickly identify and respond to potential coronavirus hot spots and outbreaks.

The tools include a COVID-19 symptom checklist web application and COVID-19 dashboard that provides real time, visualized data for officials to easily identify areas where the new coronavirus presents a higher risk, and for the public to understand the pandemic status in their community and across the state.

“We need to find safe ways to reengage with our communities so that we can mitigate the spread of disease and risk while still allowing us to resume some level of economic activity. In order to do that, we need real-time information on the movement of the epidemic throughout the community so local and state officials can make informed decisions on how and where to reengage,” said Emily Martin, a professor at the U-M School of Public Health. “Unfortunately, this is an epidemic that could be with us for a very long time.”

Collaborating to save lives and livelihood

epidemiologist Marisa

Eisenberg’s rough drawing

that inspired the dashboard

design.

Since the pandemic broke out, a team of experts from U-M’s School of Public Health have been working closely with the state’s departments of Health and Human Services and Labor and Economic Opportunity, providing expertise in modeling and forecasting data, identifying different stages of the pandemic to inform state’s closures, and working closely with industry leaders to evaluate risk factors for different working settings and coming up with risk-mitigating strategies to reopen those workplaces.

After identifying the need for up-to-date health-related information throughout the state’s population, the team invited participation from colleagues from Michigan Engineering and U-M’s School of Information who have the expertise in developing apps, product design, user experience and data protection to develop the tools.

“We’re using a precision population health approach, using data, key public health indicators and technology to help the state manage this pandemic and reengage the economy safely,” said project lead Sharon Kardia, professor of epidemiology and associate dean for education at U-M’s School of Public Health. “My hope for the people of the state of Michigan is that we can go back to work safely, that we can actually enjoy some of the beautiful summer that’s coming, and that we can do this while paying attention to the ways in which we may be at risk so that we can actually counter that risk.”

How are you feeling today?

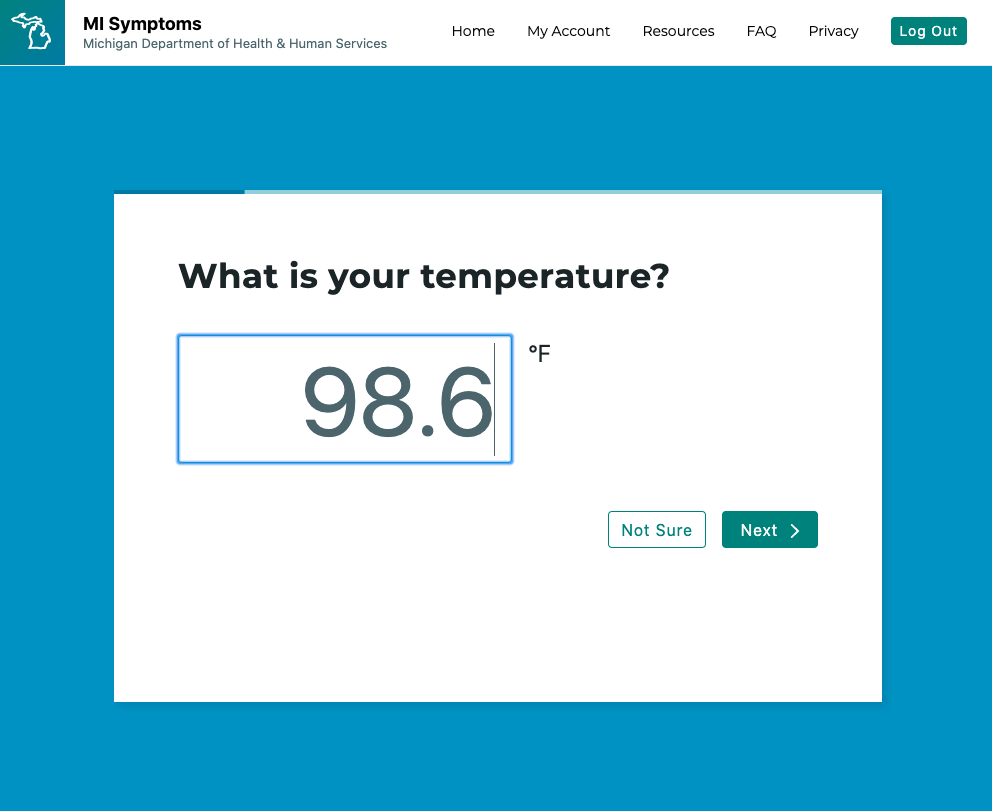

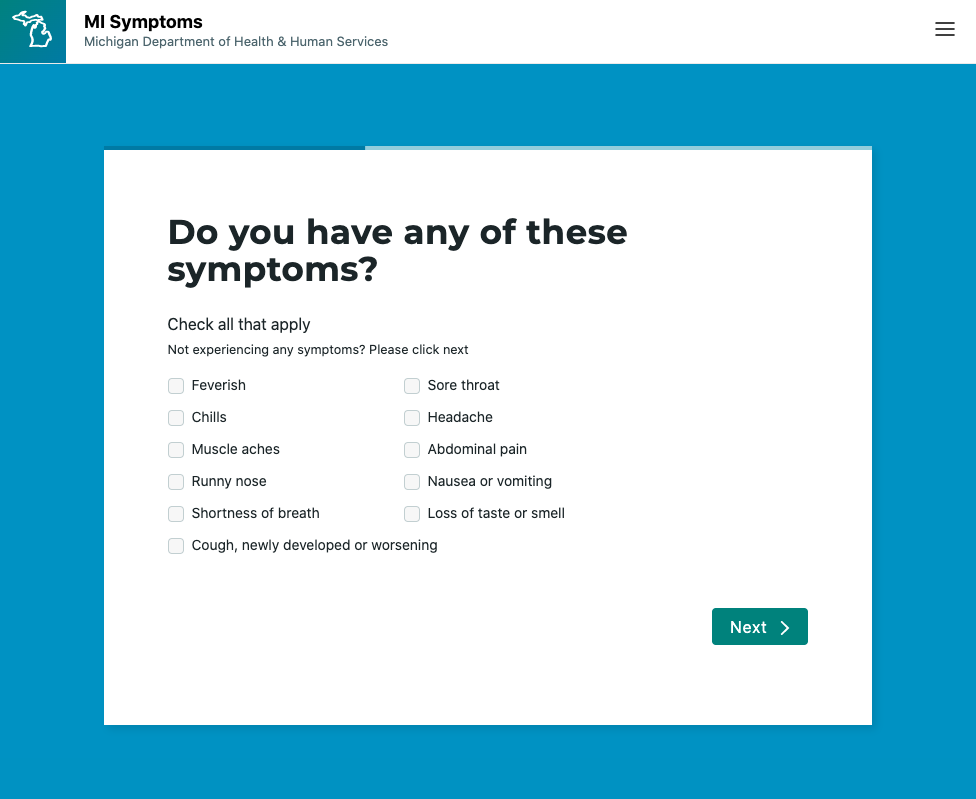

The web app, called MI Symptoms, is designed to be used on a daily basis as Michiganders head back to work. Some employers may ask or require employees to use it to help identify potential cases of COVID-19 before it can spread.

It includes questions such as: How are you feeling? Is anyone in your household sick? Have you been around anyone who tested positive for COVID-19? Users also enter their body temperature and review a list of COVID-19 symptoms, checking off any they’re experiencing.

While other wellness apps and websites can monitor COVID-19 symptoms, the U-M developers say theirs is unique in that it was built with a focus on security and it has a singular goal.

“This is purpose-built to support the state of Michigan’s reopening in a safe, measured way,” said Dan Maletta, executive director of information technology at Michigan Engineering who co-led the web app’s development.

“There are a number of other apps that exist to collect this information. In many cases they are developed by private companies and they may not share data with the state and university and could even use some of the data for their own purposes.”

While MI Symptoms will be accessible through mobile devices, it is not a mobile app. It will not be used for contact tracing, and it will not track users’ locations or movements through GPS or Bluetooth. Even if users choose to sign in through Facebook or Google, it will not share any information with those companies.

Security was paramount throughout development, Maletta said.

“We have taken measures to isolate the information coming through the app and separate it from any personally identifiable user data,” he said. “We will also only store the most anonymized version of data.”

Showing the work

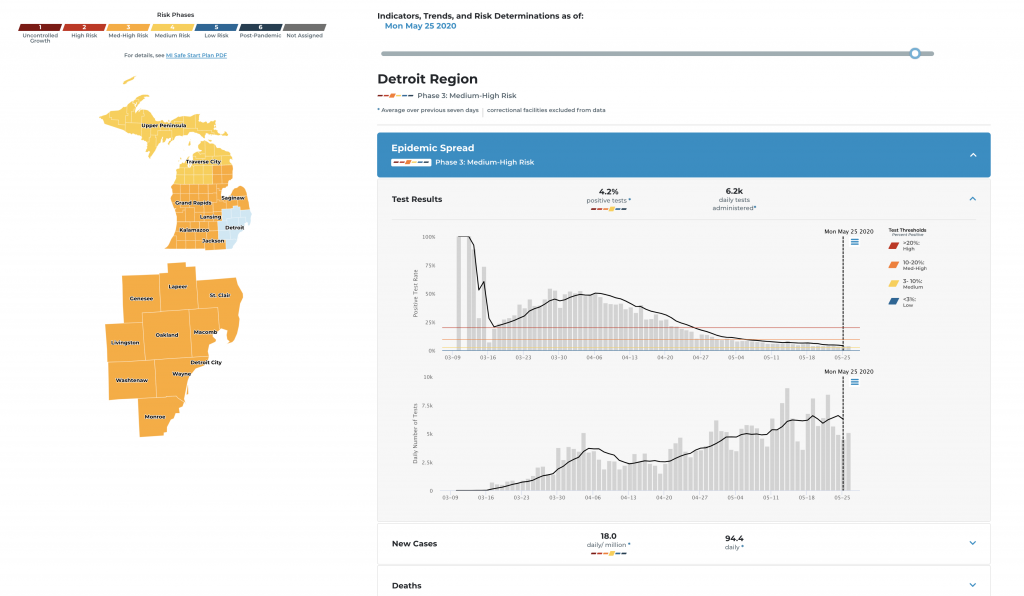

The MI Safe Start Map dashboard development was led by the U-M School of Information in partnership with the School of Public Health, involving dozens of faculty, staff, students and alumni.

The goal is to help state leaders “balance lives and livelihoods” as they determine when it is safe to resume various activities as the state emerges from the current stay-at-home directives, said Paul Resnick, professor of information and associate dean for research and faculty affairs at the School of Information.

“Given there are many indicators that could show something is going wrong, you want a way to systematically monitor them, calling people’s attention and having them then go and investigate something before making the difficult decisions about when to reopen what.”

Using procedures developed by epidemiologists Emily Martin, Marisa Eisenberg and Jon Zelner at the School of Public Health, the dashboard uses key public health indicators such as number of daily new cases per million residents and percent positive tests to help local and state public health officials identify and track hotspots that require further attention. A scaled-down version for the general public lets people look up the current risk phase of their region and see some of the underlying indicators that contributed to officials’ determinations.

The MI Safe Start Map for health officials includes both levels and trends in indicators such as numbers of new cases, deaths and positive tests that reflect the most up-to-date data distributed to the School of Public Health from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Another indicator comes from MI Symptoms. It also tracks health system capacity and public health capacity, such as availability of tests and trained contract-tracing personnel.

The public-facing dashboard uses a color-coded map of the state with breakdowns by region and county. Each area is labeled with the current status of the virus to show where the coronavirus is most active and where it is more under control, based on the data.

Common goals

In all, more than 80 staff, faculty members and students from engineering, information and public health contributed to the app and dashboard development. The groups worked nearly around the clock in various teams, seven days a week since joining the project April 20.

“These students put their heart and soul into the code,” said Elliot Soloway, professor of computer science and engineering and professor of education. “A lot of them have an emotional connection to the COVID crisis. People they know are sick or have passed away so they want to do this and they want to do a good job and they want to do it now.”

UMSI students involved included a 2020 graduate who served as project manager, responsible for recruiting and onboarding new members, and making sure everyone had the tools needed to do the work. Emil Meireles called his involvement with the project “exciting and humbling.”

“I think one of the main things I learned from this is that the fight against COVID-19 will need to be fought through data as well as medicine,” said Meireles, who graduated this semester with a Bachelor of Science in Information. “When a pandemic takes a state by storm it thrusts our government and people into a stressful and ambiguous situation tools like this dashboard help to make sense of situations like this and help inform critical decisions that impact people like me. Likewise, it helps to ease the fears of the public because it allows them to have a better understanding of why those decisions were made.”

Alex Fidel, one of the co-leaders of the User Experience (UX) Team and a recent Master of Science in Information graduate, said his degree and a graduate certificate in health information prepared him well for the work.

“It wasn’t intimidating. The notion that we get to build a tool for the state to use is humbling—it says something about the Michigan Brand—but I felt prepared and confident we could together build something that could rise to the challenge.”

Fidel said the team created more than two dozen iterations of the dashboard, altering it based on user experience, which included recruiting epidemiologists from SPH to try it out. The team gave the users challenges to see how they would respond to the data presented, and sought input on how easy it was to understand the information.

Cassandra Eddy, who served on the web team, said a keyword when creating a tool like the dashboard is “agility.”

“It did feel pretty big. There are no requirements in advance so the team had to be very agile. The features are changing every day,” said Eddy, a graduate with a Master of Health Informatics, a joint program between the schools of information and public health. “It’s been incredible to work with such talented people.”

Ani Madurkar just completed his first year in the Master of Applied Data Science program at the School of Information, during which he chose to work on how demographics like wealth and population impact COVID. This caught the attention of information faculty who nominated students for the team.

His girlfriend works as a pharmacy resident on the front lines at Cleveland Clinic, which he said inspires him to use his skills to “serve a larger purpose.”

“I feel a huge sense of responsibility for it. Data scientists should be cognizant of the impact they have in society,” said Madurkar, an IT data analyst in Okemos, Michigan.

“I think that there is a sense of validation that will be there,” he said of the prospect the state would use the tool. “It’s exciting to see what this could mean for the future of health and technology.”

Kardia said the sense of responsibility and urgency was very real for the whole team.

“This pandemic has many of us very scared that if we don’t act now and we don’t act with the best science behind us, then we’ll end up with an unintentional disaster on our hands,” she said. “There’s a great sense of urgency and my colleagues and I have put all of our best time and attention, best mind, heart and body toward this effort.”