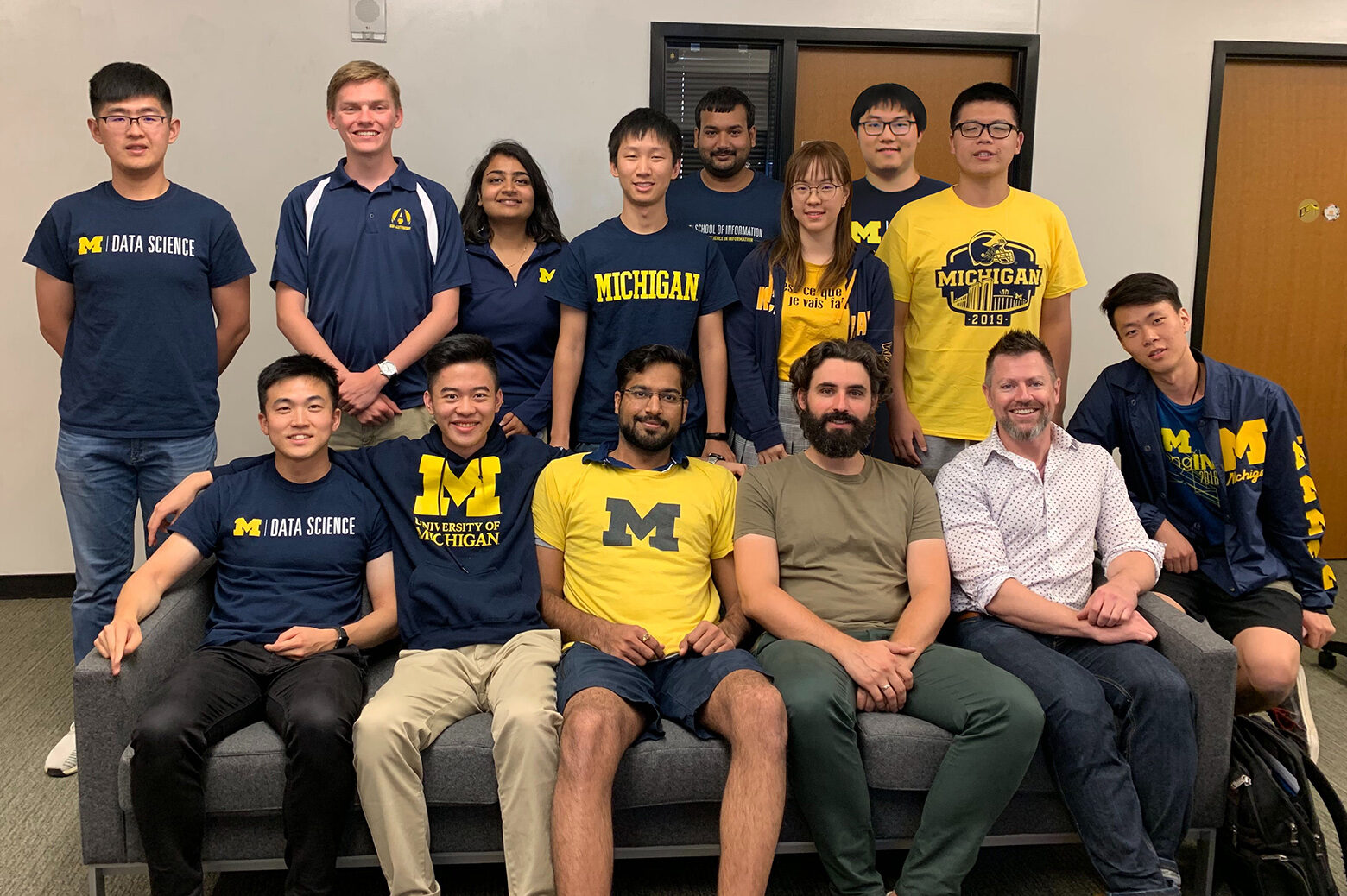

Photo by Wook Suk Seo, doctoral student at School of Information.

“Hi, this is an Alexa Prize Socialbot. Welcome back. I hope all is well. Random question: what is that one thing you want to do today?”

“One thing I want to do today,” I say, “well, I’m going out with some friends tonight.”

A few seconds go by, and the rim of the Amazon Echo shimmers blue, as if she’s thinking. “That sounds fun. I would also want to go,” Alexa says. Over her voice bursts the chorus of Taylor Swift’s cheerful anthem, “22.” Is this Alexa’s way of telling me she wants to get involved with the fun too? Or has she somehow already figured out that I’m 22?

“I’m sorry I can’t take you,” I say.

“Let me know if you are able to,” she tells me.

Now laughing, “I wish it was a possibility, Alexa,” I say, “how are you?”

Then Alexa says, in a way I can only describe as sweetly: “Better now that I’m talking to you.”

Chat with a robot

Think about the last conversation you had. Was it with a friend, a colleague, a stranger? Did you talk about the news, sports, entertainment, politics? Did it feel transactional — or engaging? Forced — or seamless? Did it feel like the other person was listening? What made it successful?

The main tenant of a conversation is that it’s an exchange, a back and forth sharing of thoughts, feelings, information, in which its success is equally weighted on both parties involved. Conversations are something we traditionally view as purely within the realm of human-human interactions, but what if you could have a conversation with someone inhuman, and it could be equally, if not more, fruitful and enjoyable?

That is what University of Michigan’s Alexa Prize Socialbot Grand Challenge team is attempting to create.

Photo by Wook Suk Seo, doctoral student at the U-M School of Information.

The Alexa Socialbot Grand Challenge 3 is a university competition to further the capabilities of Artificial Intelligence (AI) by building a conversational Alexa skill. Teams are tasked with creating a socialbot, a robotic automated program that can have conversations about popular societal topics and current events. The overarching goal is to develop a socialbot that can effectively engage in a conversation for 20 minutes while earning a rating of at least a 4 out of 5; however, the team with the best socialbot will win regardless of reaching that goal.

Teams from around the world submitted applications to the challenge in May 2019. Out of hundreds of entries from 15 countries, 10 teams were selected, including one from the University of Michigan. The U-M team comprised of 11 graduate and undergraduate members, 4 UROP students, and 2 co-advisors, School of Information Assistant Professor David Jurgens and School of Engineering Assistant Professor Nikola Banovic.

The U-M team has been competing since the beginning of the academic year: starting in September, they were tasked with developing their socialbot within a month’s time to submit for evaluation by early October. For the rest of October, the teams were able to fine-tune their socialbots to ensure the bots pass the certification needed to be used internally by Amazon employees and ultimately, by Alexa customers.

After a Beta Period in November, the socialbots, including U-M’s creation named Audrey, went live to customers in December. That means that every time Alexa customers say “Let’s Chat,” they trigger the Alexa skill for the competition and will be randomly connected to one of the 10 team’s socialbots. After the conversation, the users are able to rate the experience. The beauty of this competition is that the teams get feedback from real customers with topical interests.

“One of the unique parts of this is that in normal academia, if we want to build a chatbot at my lab, we would have to recruit all these people to come chat with us and maybe we’d get a few hundred people,” Jurgens said, We are getting that many or more every day, and we get this huge diversity in the kind of conversations we have.”

What conversations can a bot have?

That has been an ongoing process. Audrey is able to discuss with Alexa customers on music, movies, and news, among other random topics. If a customer wants to talk about the news, the Audrey team has created algorithms that utilize headlines and titles data to summarize articles, resulting in a fruitful discussion on current events. If a customer wants to talk about a movie, Audrey mixes up facts from an array of sources to make the conversation more diverse and interesting. As Audrey has more and more conversations with a diversity of people, the group has been able to meet their interests.

“I think it’s our job to help steer that conversation,” Jurgens said, “[and] find a way to kind of signal to the user the kinds of things that we were able to chat about and to have a conversation about those really well, so they feel satisfied and rewarded for that discussion, but aren’t like, why don’t you know abstract mathematical topology? We’re not going to do everything.”

The U-M team is structured into three functional groups: understanding users, generating sentences and dialogue policy. The ‘understanding’ topic group works to ensure the socialbot comprehends what the customer is trying to say; the ‘generating’ segment makes generation models to create new sentences in response to the customer’s words. The ‘dialogue policy’ segment functions as the brain of the socialbot, and selects, among the several generated, which response is the most appropriate to say back to the customer. All these groups work together to make sure each and every Alexa customer is getting the best experience out of their conversation with the Audrey socialbot.

“What Amazon has taught us is to focus relentlessly on the customer,” said Chung Hoon Hong, team lead and 2nd year data science master’s student in the department of statistics, “We look at how the conversations have turned out and try to improve upon that.”

If the conversation with Audrey goes poorly, the group assigns people to work on the problem based on their functional group. For example, if the issue is rooted in the generator, or if the bot isn’t comprehending cues and there might be something off with the understanding model, the work is allotted to the appropriate group.

“One solution hasn’t solved everything,” Hong said, “We have to tweak things, so every day it’s a challenge, something new is always coming up.”

Working out solutions takes time

The members of the team work anywhere between 10-30 hours a week, including a weekly meeting every Tuesday and work sessions on Saturdays.

“It is a lot,” Jurgens said, “and certainly a lot of students have learned about time management and juggling responsibilities from having to keep an active socialbot online.”

While a huge commitment, for the students involved this is an exciting new opportunity.

“For me, I’ve never done anything on the magnitude in terms of usage, impact or as large of a project before,” Zhizhuo Zhou, EECS computer science sophomore, said, “this is an opportunity for me to try something and get experience with something way bigger than anything I could have done myself and with the team, we are able to do it.”

While building a socialbot has its challenging moments, creating something where students have a direct impact on real customers and interactions has been more than thrilling.

“My favorite part is seeing Audrey, our socialbot, have a successful, or even just funny, interaction,” Ryan Draves, EECS computer science junior said, “sometimes it feels like happenstance, other times it feels like it’s coming together and that we really have an intelligent system.”

The finish line

As of Feb. 3, the Audrey team is in the Quarter-Final Stage which ends Mar. 17. During this round, teams will be divided into two brackets and the three top socialbots in each bracket (six teams) with the highest average ratings will move on to the next phase. All teams are invited to the Alexa Prize Summit held in March 2020 in Seattle, Washington.

Regardless of whether the U-M team moves on or not, members say the process has provided many lessons.

“This competition has been a tremendous learning experience for me,” Sagnik Sinha Roy, data science Master’s student in the school of information, said, “It has helped me to understand neural network based generative models better, as well as how to work effectively in a team so as to maximize output.”

“We get to work on a problem that’s not solved yet,” Hong said, “Working on this has made me realize how hard of a problem this is and there’s a really long way to go in terms of natural language processing. When you hear about AI taking over the world,” Hong laughs, “it’s not that easy!”

The winning team will be awarded $500,000; the second and third place teams awarded $100,000 and $50,000 respectively. If the winning team is able to accomplish the Grand Prize of their socialbot conversing with users for at least 20 minutes with a 4 out of 5 rating, their university will be awarded a $1 mil research grant.